de broglie-bohm theory

an alternative interpretation of quantum mechanics

dead

“Of course it’s dead!” Schrödinger argued, “The cat has been locked in a box for quite some time now. There is no way it is still alive. What else in the world could survive so long in such conditions?”

“Absolutely nothing I would say. But until someone opens the box there is no certainty to your claim. The truth is we have no idea. It could be alive. It could be dead. It’s both until we know for sure,” Bohm responded.

“How absurd,” Schrödinger hastily rebuked. The truth was, he believed this too. In fact, he only trapped his cat in the box to underline this absurd notion. “Alive and dead is such a ridiculous claim. It’s either one or the other. That’s the narrative!”

“Say what you will but we will never know until someone opens the box. For now it is alive and dead. That is what the math tells us.”

“Well, that does not sit well with me.”

Schrödinger dropped the chalk and walked away from the board. Written on the chalkboard was his famous equation surrounded by derivations, drawings and graphs. All of which Bohm had used aggressively to prove the unintuitive ramifications of Schrödinger’s theory. As the tension grew between the two a third voice joined in, hoping to placate the growing acrimony.

“Perhaps there is another way of interpreting the situation?” de Broglie suggested, “Life does has its narratives. We cannot avoid them. Things tend to be concretely one thing or another. Rarely do we see a mixture. There might, however, be a subtle reality where we do. A reality that we are not privy to but fundamentally defines our experience. So allow me for a brief moment to posit a different understanding.”

narratives

“Our lives are defined by narratives,” de Broglie continued. “This morning I woke up, grabbed a coffee and walked to work. It all made sense. One thing lead to another and a narrative organically emerged.

This is how we interpret our lives. Cause has effect. There is always a narrative explaining how things become what they are.”

“Then the cat must be dead,” Schrödinger declared. “The cause is the box and the effect is death.”

“True,” Bohm responded. “But we cannot ignore the mathematics of the Copenhagen Interpretation which tell us quite distinctly that we do not know which state the cat is in.”

De Broglie intervened, “Of course we cannot. But neither can we ignore the causality we experience everyday. We naturally apply a narrative to our lives. When a cat can be both alive and dead we lose that narrative. The idea of losing the sense of certainty we are otherwise defined by makes quantum mechanics uncomfortable for many. Let me explain.”

rubble

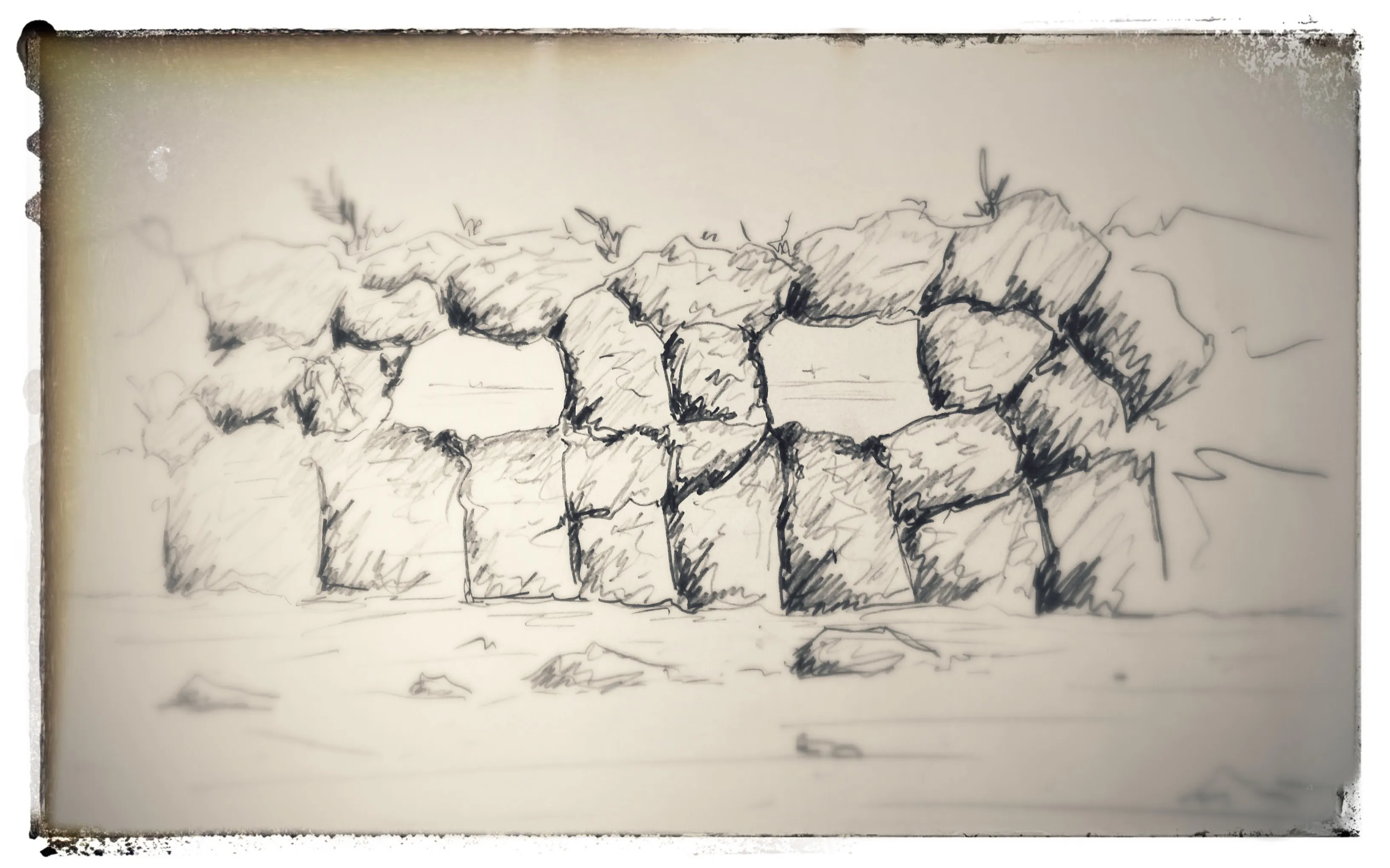

“Imagine a wall in front of us,” de Broglie continued. “It is tall and strong. Moss grows within the masonry weathered by the years. To the left it extends beyond the horizon and to the right just as far. Two openings nested in the structure open to a flat, serene landscape. Fallen remnants of the aging wall lay as rubble at our feet.

The wall that extends beyond the horizon with two openings nested in it.

The wall that extends beyond the horizon with two openings nested in it.

One by one we pick up the bits of rubble and chuck them at the wall. With every hit we hear a light crack. Every once in a while a rock passes through an opening and we hear it softly land on the other side. After we throw two hundred rocks we peer through the masonry and notice two piles of stones and intuitively understand why. The pile on the left are the rocks that passed through the hole on the left and the pile on the right are the rocks thrown through the hole on the right. There is a narrative that explains the rocks. A story our brain can put together. It makes sense.”

“This is why Schrödinger argues that the cat is dead,” Bohm said. “The problem with your story is we see the rocks. We don’t see the cat.”

“True, but let us proceed with the analogy before delving into the subtleties,” replied de Broglie. “We continue walking along the wall. Again we encounter a similar situation. Rubble on the ground, two openings in the wall and as we peer through them we can make out the same serene landscape.

We grab the rubble again one by one to throw. This time, however, we close our eyes and spin around before each throw. We chuck a stone. Crack. It hits the wall. We do it again. And again. And again. Each time with our eyes closed. Each time we spin. With each throw we either hear a crack or the rock landing on the other side. Eventually, we run out of rocks.

As we stagger up to the wall and peer through, shockingly, we do not see two piles of rocks as we did before. This time we see many piles. We pat ourselves on the head, rid the vertigo and look again. Still there are many piles and not just two.

The pile of rocks we see. This time there are multiple piles. A large center pile is in the middle with symmetrically smaller piles to its sides.

The pile of rocks we see. This time there are multiple piles. A large center pile is in the middle with symmetrically smaller piles to its sides.

One large pile rests in the center with symmetrically smaller piles spanning to the left and right of it. We do not intuitively understand why this time. We threw the rocks just like before. We heard them land just like before. There’s only two paths for the rocks to take. The narrative should be the same as before but the piles are different this time. So what is the difference?”

Bohm responds, “Well, much like the cat in that box, nobody actually saw the rocks fly through the air this time. Our eyes were closed when we threw the rocks. We only know two things for certain: the rocks were in our hand and the rocks landed were they did. And just as we cannot see the cat, the narrative is lost and the reality isn’t what we expect.”

“Could simply closing our eyes have such an effect on our reality?” Schrödinger questioned. “All our experience rejects this notion. Just like I argue that the cat is dead, I would argue that the rocks should always land in the same two piles. It appears they do not though. This cannot actually be reality.”

“But it is reality!” Bohm exclaimed. “This, as I’ve been saying, is what the Copenhagen Interpretation asserts. Again, I argue, the cat is both alive and dead.”

“It is counterintuitive,” de Broglie continued. “Do not be alarmed though. This does not sit well with others either, Schrödinger. I mean, does it make sense to have more than two piles regardless of the circumstances? No. But it does happen.

When our eyes are open and we watch which hole the rock goes through the rocks end up in two piles. This makes intuitive sense. There is a cause and effect relationship. One thing leads to another. This is the certainty. By this reason, Schrödinger, the cat is dead.

When we have our eyes closed, however, the rocks land where they could have landed. We did not witness a narrative and therefore have no clue how the rocks flew through the air. They could have floated around a while, changed directions mid-flight or briefly vanished because we just don’t know. We can’t. Our eyes were closed. And by this reason Bohm is correct in assuming the cat could either be alive or dead.

The multiple piles are there because that is where the rocks were most likely to end up landing. Without hard evidence of their trajectories we cannot determine where the rocks will land with certainty. All we know is where the rocks could land. And the rocks could land in those multiple piles so that is where they end up.

The conflation of the could be with the reality of multiple piles is unsettling. Statistics have somehow become the apparent reality.” “Now we’re entering into the murky arena of possibilities,” Schrödinger interrupted, “but I still maintain that even though we didn’t see the rocks being thrown there must still be a narrative. Just like the cat in the box, we don’t know if it is alive or dead, but I still argue that regardless of its state there must be a narrative that explains the cat as it is right now.”

paths

“It’s great that you say that,” de Broglie responded. “That is exactly what I want to explain next.

The problem with Bohm’s adamant belief that the cat is both alive and dead is that it goes against intuition. Which is okay. Although there could be an alternate explanation that mollifies this feeling.

Quantum mechanics can be looked at from different perspectives. Imagine a coin. Describing each side independently yields different descriptions but a few characteristics would overlap, such as its shape or its material. In the end it is still the same coin being described. Let’s go back to the board and ponder Schrödinger’s equation again.”

De Broglie walked over to the chalkboard, grabbed an eraser and smudged away everything but Schrödinger’s equation.

“Let’s attack it from a different angle,” de Broglie said.

After some quick derivations the board yields another solution. One that is strange to both Bohm and Schrödinger himself.

De Broglie continued, “The argument goes like this. Although we do not know how the rock flew passed the wall we can still infer a path. This path, like any other path, is defined by a starting point that predicts its destination. Each rock we threw followed a path. We just did not see it happen. With this derivation we can not only assume the paths but we can calculate them.”

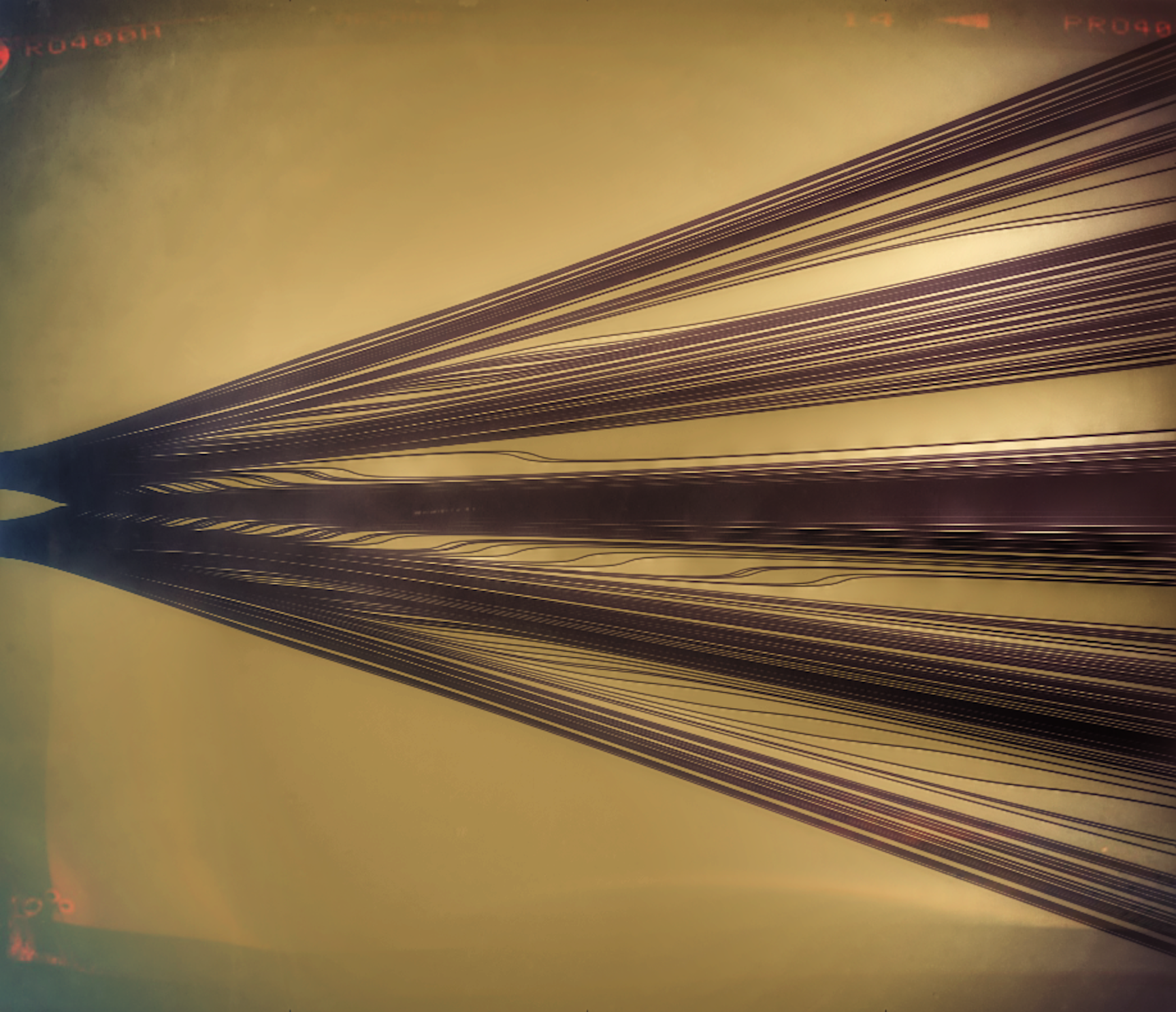

De Broglie quickly jots down calculations for hundreds of rocks thrown at the stone wall. With each calculation he draws a line on a graph representing the path that rock has taken before it lands. Hours go by. Finally, Bohm and Schrödinger begin to see a pattern emerge.

The paths of two hundred rocks thrown through the wall.

The paths of two hundred rocks thrown through the wall.

“After throwing two hundred rocks this is what the rocks’ paths look like from above,” explained de Broglie. “Each line represents the path of a rock as it passes through the wall on the left, travels through the air and lands on the right. Notice on the left all the rocks come from one of the two holes in the wall.

Also, the paths have a few noticeable characteristics: they are not straight, they never cross and they tend to coalesce into groups the farther away from the wall they travel. These groups are the piles where the rocks landed.

A narrative is starting to form.”

wait

“Hold on a second,” Bohm said, “Those are some puzzling characteristics. Why do the paths curve? Shouldn’t they be straight? We have never seen a rock change trajectories mid-flight for no apparent reason. They always travel straight.”

“All true,” responded de Broglie. “Although, remember just because we’re applying a narrative doesn’t mean the narrative has to be intuitive. This is still quantum mechanics we are talking about here.”

“At least there is a narrative,” Schrödinger said, “although, the narrative is not as conceivable as I had hoped. Why do these paths curve and never cross?”

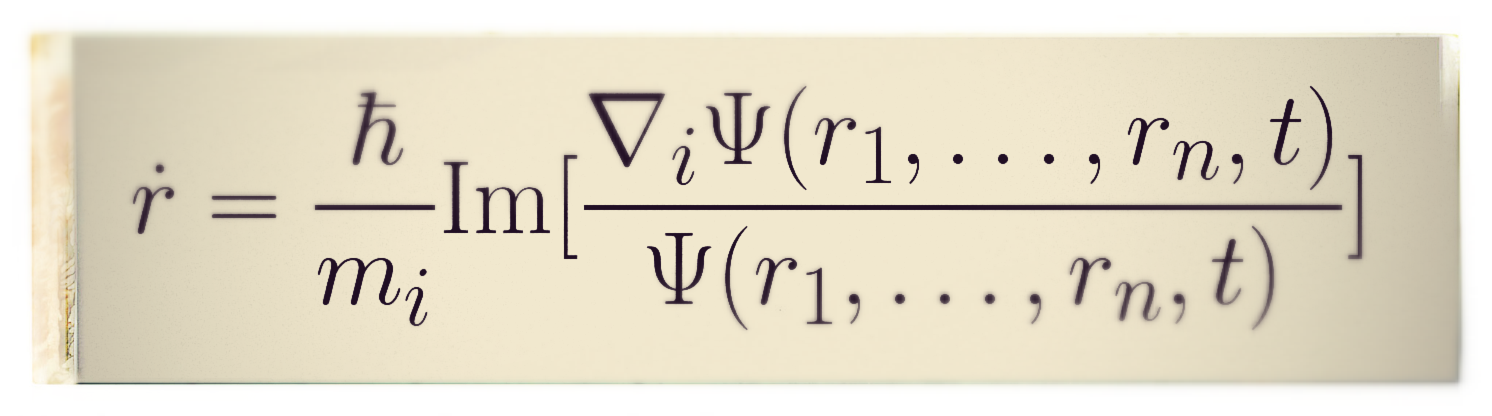

“Good question. The curved trajectories are calculated by this equation,” de Broglie responded pointing to the chalkboard.

“Just take a moment to realize how elegant this equation is,” he continued. “It is short, concise and explains precisely why the paths curve. That is a incredible notion. Furthermore, we can infer from this equation that the curved paths are an intrinsic remnant of the probability engrained in the entire quantum mechanics theory. The statistics of quantum mechanics still exist and from this comes the curvature of the paths.”

“So there is still some statistics involved?” Schrödinger asked.

“Yes and the paths represent those statistics,” replied de Broglie. “Remember the coin I explained earlier. Looking at each side would yield different descriptions yet some characteristics overlap. The curved paths are analogous to those similar characteristics. They are an overlapping attribute of the different quantum mechanics interpretations. Nothing more, nothing less, but just as real.”

implications

“Anyone who has taken basic quantum mechanics knows there is nothing terribly new here,” de Broglie continued. “Of course the rocks pile up like that! The Copenhagen Interpretation already tells us that.

The only difference now is a narrative exists. The rocks have a path defined by an equation. It doesn’t predict anything new but it doesn’t contradict anything old. This is something the Copenhagen Interpretation does not quite do.”

“Well this new interpretation appears to work with the situation you described but what about other scenarios?” asked Bohm.

“It still holds true,” de Broglie responded, “and some scenarios are quite peculiar.

Let’s say we grow tired of the wall. We grab a handful of rubble as we depart and say farewell.

The two of you, Schrödinger and Bohm, decide to start throwing the rubble in front of you as far as you can. I stand aside and watch. As Schrödinger throws a rock, Bohm tests to see if he can hit it out of the sky with a rock of his own. I watch as he throws his rock and miraculously hits Schrödinger’s out of the sky. Now each time either of you two throws a rock the other tries to hit it out of the air mid-flight.

The rocks land and pile up as the two of you continue. I watch and know exactly which rock lands where and exactly which path each rock took. Everything is predictable and I witness the narrative as it happens.

Now I close my eyes.

When I reopen them I notice the piles are bigger. More rocks have been thrown. However, I do not have any knowledge of which rock landed where anymore. Additionally, I have no knowledge of the trajectory each rock took. I have lost the narrative.”

“We could just tell you which rocks landed where,” Schrödinger said.

“Yes, but that would be cheating,” quipped de Broglie. “There is a better way, I can calculate the trajectories just like I did before.”

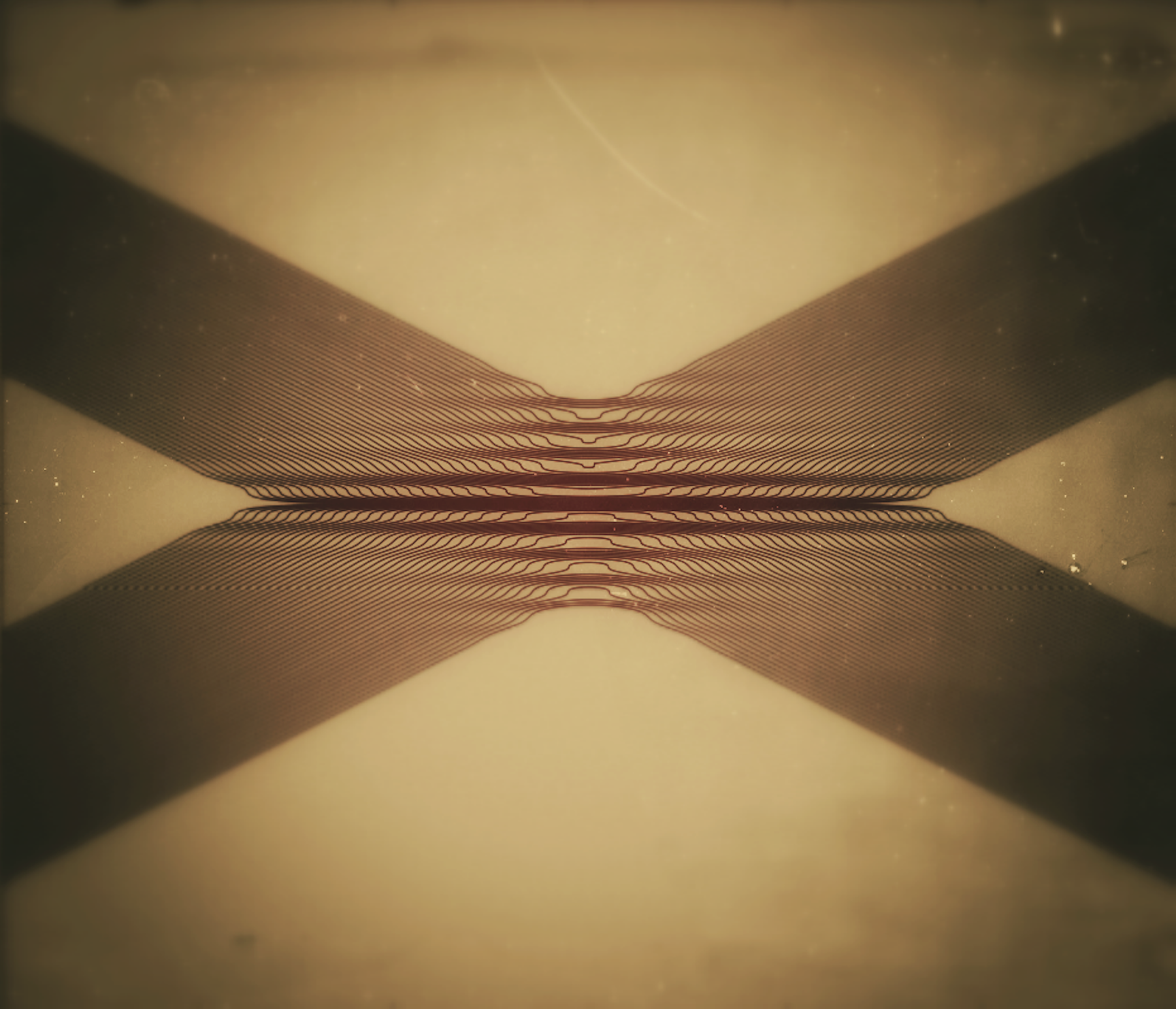

De Broglie erases his previous work from the chalkboard and begins calculating a brand new set of paths. This time for rocks being thrown towards each other. A pattern emerges once again.

The path of one hundred rocks thrown towards each other.

The path of one hundred rocks thrown towards each other.

De Broglie explains, “This is what the trajectories look like from above. Each line represents a rock as it travels through the air, hits the other rock and reflects back. Let us say Schrödinger was standing on the top left and Bohm on the bottom left part of the graph. The rocks were being thrown towards the center of the chart. After throwing one hundred rocks notice that the paths share the same characteristics as before: they curve and they never cross.

Looking at these trajectories we can conclude that as the rocks enter in from the left of the graph they deflect off each other in the center of the graph and head back the way they came.”

oddities

“They don’t look they hit each other at all though!” Bohm remarked. “The center of the chart is too dense to see but other paths appear to just curve back around on their own, like the bottom-most path.”

“Very true and this is an oddity that emerges from calculating the trajectories,” de Broglie responded. “When we imagine throwing rocks at each other we instinctively believe they will hit each other. If we look at the traced paths, however, the rocks never look like they actually collide with each other. They seem to deflect without physical contact. So how does this transpire?

Simply put, these are the paths the rock would take regardless if another rock was present to deflect off of.”

“So what if just one rock was thrown?” Schrödinger asked.

“It would deflect off of nothing,” de Broglie responded. “More precisely, it would deflect off the probability of another rock being there.

Remember what we learned from the wall. If we knew which hole the rock passed through we ended up with two piles of rocks. There is a narrative because we witnessed it. When we did not know which hole the rock passed through we ended up multiple piles of rock. The narrative had to be inferred. Therefore, the narrative must be dependent on these multiple piles. And these multiple piles are where the rocks are most likely to end up. The probability is, therefore, ingrained within the inferred paths.

Now apply this to throwing the rocks towards each other. If I know who throws the rock I will watch it fly through the air and land in the dirt. There is a narrative that I witness. However, if I close my eyes and do not know who throws the rock I lose the narrative. I can only infer it. The narrative, however, is still fundamentally dependent on the probability of where the rocks could have landed. The paths, therefore, are defined and guided by their statistics.”

alive

“So do not ignore the notion of alive and dead, but more importantly, do not dismiss a narrative,” said de Broglie. “As I entered this conversation I merely wanted to introduce a new perspective on the quantum world. One that encompasses both statistics and certainties. The narrative it provides may not be intuitive but it exists. It can be calculated.”

“So is the cat dead?” Schrödinger asked.

“I gather that we do not know,” said Bohm.

“Precisely,” responded de Broglie. “The cat may be dead or it may be alive. Either way, a narrative will exist when we find out.”

All graphs and more can be recreated with the following Python scripts. Read my paper for a more mathematical approach to this concept.

Originally published on my medium page